We Honestly Love You

20s

By Matthew Paroz

Olivia Newton-John was one of the finest pop performers that Australia has ever claimed as its own, with a talent that earned her almost every accolade imaginable — Grammys, chart records, country music awards, movie stardom and more.

Her death this year brought many memories of our Livvy

to the surface, along with a fresh appreciation of her humility, her music, and the path she forged as an international superstar.

As a kid, like pretty much every other Aussie kid of a certain generation, I had a terrible crush on Olivia Newton—John. Bright and ethereal, she seemed to me to be the most beautiful human to ever grace the planet.

To that little boy, Newton—John was a superstar goddess, yet she also exuded genuine warmth, an accessibility that few in the public eye possess — particularly now, in the era of modern celebrities trading in on a confected, social media—driven brand of authenticity.

Livvy, as we called her, was authenticity personified. No matter how famous she got, no matter what life threw at her, she never lost that quality. That her genuineness remained part of her public image until the very end is proof, if any were needed, that the person she showed us was the real deal.

As talented as Livvy

was, surely even she couldn't fake such a convincing performance for seventy-three years. The way Olivia made you feel was that if you bumped into her at the supermarket, she’d greet you with that incredible smile and envelop you in a hug like an old friend would.

I never got to find out for myself, but when my grandmother returned from a trip to the United States in 1985, she brought back something that felt just as special to me: a white t—shirt, several sizes too big, procured from Olivia’s Famous Koala Blue Aussie Milk Bar

in Los Angeles. I was rapt. As I unfolded it, my jaw dropped. There, under the cheeky illustration of a pink and teal koala drinking a milkshake, was an inscription scrawled in Sharpie. To Matthew, love Olivia.

I could have died happy at that moment. The thing is, even though that little boy knew this woman was special, he didn’t appreciate her significance as a pop pioneer. And, all these years later, I still don’t think many people do.

Don’t get me wrong — the extraordinary outpouring of love and hopeless devotion to Australia’s sweetheart in the wake of her passing last August was heartfelt and very much deserved. In the days following the news, it seemed almost everyone held a special memory of Olivia Newton—John, and a fondness for her. It was testament to the fact that nine—year—old me wasn't the only one she made feel special: apparently she had that effect on millions. A gift indeed.

But what seems to have been largely overlooked among the thousands upon thousands of column inches feting and memorialising Qlivia Newton—John is the way in which she pushed boundaries, shifted perceptions and did the kind of things many of pop’s biggest innovators did, except she did it long before most of them ever picked up a microphone.

Now seems like an appropriate moment to set the record straight.

Funny things happen

You’d have to imagine that those who knew her way back when must have sensed she was destined for greatness, even if they couldn't have predicted the spectacular career she would carve for herself, one that's permanently etched in pop cultural history. I mean, a Melbourne schoolgirl with the talent (and gumption) to form a girl group at the age of fourteen is the kind of someone who’s going places.

Sol Four, as the band was known, didn't last too long by all accounts, but Newton-John continued her proclivity for performance on stage at high school.

Before long she became something of a fixture on television variety and talent shows, even landing a role in her first film. It's fair to say Funny Things Happen Down Under (1965) has the most batshit—crazy synopsis of any film bar Xanadu (more on that later): it was a musical about kids singing in a barn and dyeing sheep to save a farm.

That same year, she was victorious on TV contest Sing Sing Sing. Her prize? The chance to jet off to record a single in the UK, incidentally the very country where she had been born seventeen years earlier . . .yes, it's true,Our

Olivia was an import, but we Aussies aren’t shy about claiming anything we love as our own and turning them into cultural icons (a tip of the hat to Naomi Watts, Russell Crowe and pavlova).

Even though that first single, a track called Till You Say You’ll Be Mine, didn't make a blip on the charts, Newton—John stayed in England, gigging with fellow Australian singer

Pat Carrol] as Pat and Olivia

in European nightclubs and as back—up for other musical acts. She even ventured back into the studio as part of the short-lived pop group Toomorrow.

Newton—John wasn’t destined to share the limelight, however, so when she again recorded as a solo artist at London’s famous Abbey Road, no less, it was time for her star to really shine.

Her 1971 debut album If Not For You (or Olivia Newton—John, depending where you lived) was a collection of covers and spawned two hits. The Bob Dylan—penned title track topped the Billboard Adult Contemporary chart and climbed to the top 25 on the Hot 100 (number 14 in Australia).

Follow—up Banks of the Ohio, a nineteenth-century murder ballad, was an Australian number 1. Both songs cracked the top 10 in the UK.

The distinctive musical twang of those early songs pegged Newton-John as a country act, a sound that carried through to follow—up albums Olivia (1972) and Let Me Be There (1973), the title track of which, an original composition, became her first top 10 hit in the US.

If you needed some kind of gauge of Olivia’s musical bona fides, that song went on to be covered by Loretta Lynn, Ike and Tina Turner, and Elvis Presley, most famously during his iconic 1974 live Memphis concert recording.

Let Me Be There landed Newton-John a Grammy for Best Female Country Vocal Performance. This was no small feat. As a genre, country music is inherently American born and bred in Nashville, Tennessce.'lhe idea that someone who wasn't American, let alone an interloper from Down Under, could establish legitimacy as a country artist set tongues tutting.

Yet here was a woman occupying a space where she wasn’t welcome, turning convention on its head. They may not have liked her, but country purists couldn’t ignore her after the

Country Music Association (CMA) named her 1974 Female Vocalist of the Year, the highest honour for a female country performer. So affronted were some country mainstays, led by George Jones and Tammy Wynette, that they formed their own splinter group in protest against the CMA. Presumably it was for real

country performers and it was about as successful as New Coke (that is to say, it didn’t last).

In any case, the sparkling Australian could more than hold her own against Nashville's finest, and the controversy didn’t bother her fans in the least.

Unbowed, Olivia thumbed her nose at the country music establishment with If You Love Me, Let Me Know (1975), a North American release that leant into the Nashville sound. One track, Country Girl, sounds distinctly like a middle finger from a girl who grew up in Melbourne.

The album's title track was a hit (number 2 in Australia and on the US Country chart; number 5 on the Hot 100), but second single I Honestly Love You rocketed up the charts, both the single and album garnering Olivia her first US number 1 on the singles and album charts respectively (Honestly was also an Australian chart—topper).

More Grammys followed — Record of the Year and Best Female Pop Vocal Performance — and the momentum turopelled 1975's How You Never Been Mellow to number 1 on Billboard, a mere 154 days after its predecessor had occupied the slot. It was a chart record that stood unchallenged for forty—five years until Taylor Swift did an Olivia

with her twin releases in 2020.

Mellow's title track also went to the top of the US singles charts (number 3 on US Country, number 10 in Australia), and second single Please Mr. Please reached the top 3.

Grease is the word

Relocating to the US to capitalise on her popularity, Newton-John released another four US top 40 studio albums and a greatest hits collection over the following two years.

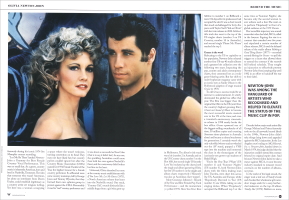

Impacting the pop, country and adult contemporary charts, they cemented her as a truly genre-blurring artist. But her shift to multi-hyphenate megastar came with an iconic turn as Sandy Olsson in the Hollywood adaption of stage musical Grease in 1978.

To call Grease a success would be an exercise in understatement. It utterly dominated the global box office that year. The film was bigger than the original Star Wars in the UK (until then the country’s highest grossing film); it beat out Sound Of Music to become the most successful movie musical ever in the US at the time; and even a twentieth-anniversary cinematic re—release in 1998 nearly broke the box office.

Grease spawned one of the biggest—selling soundtracks of all time, 30 million copies and counting (fourteen times platinum in Australia alone) and became a cultural touchstone for generations.

I certainly wasn’t the only schoolkid whose teacher wheeled out the AV stand, popped a VHS tape into the machine and immersed the class in the shenanigans of the (curiously very grown—up) students of Rydell High.

‘You're the One That l Want’ (US number 1) and ‘Summer Nights‘ (US number 5), both Newton—John duets with the film’s leading man John Travolta, were chart hits across the US, Australia and Europe, while ‘Hopelessly Devoted to You’ (US number 3) saw Olivia taking on sole singing duties.

When ‘Hopelessly’ occupied the Billboard top 5 at the same time as ‘Summer Nights’, she became only the second woman to ever achieve such a feat. She went on to perform ‘Hopelessly’ in front of a global audience at the 1979 Oscars.

Her incredible trajectory was soured somewhat when her label, MCA, called in the lawyers. Signing the star to a contract that extended over five years and stipulated a certain number of album releases, MCA used the delayed release of the studio album Making a Good Thing Better (1977) — recorded around filming for Grease — to pull the trigger on a clause that allowed them to extend the contract if the records fell behind schedule. They sought an injunction to effectively prevent Newton-John from jumping ship until 1982 in an effort to handcuff the star to their label.

Decades before major male artists like George Michael and Prince famously took on the all-powerful record labels in the 1990s, Newton—John didn’t take things lying down and appealed against the MCA injunction. In the Los Angeles court’s ruling on MCA Records, Inc V Newton—John, handed down in March 1979, the judge decided that the injunction couldn’t extend the contract beyond its original expiry date.

And because Newton-John dared to take a stance against MCA, it soon become industry standard to measure record contracts on the number of albums, not years.

In the midst of the legal stoush, the singer took a leaf out of Sandy's book and chucked her wholesome girl—next-door image aside for a sexy, leather-clad makeover on the top—1O album Totally Hot (1978). Mellow no more, the album adopted a new sound to go with the fresh look: more synths, disco-influenced drums and funk rhythms sat alongside the occasional country-infused number.

Lead single ‘A Little More Love’ hit number 3, followed by ‘Deeper than the Night‘ [number 11), both energetic pop/rock tracks. Despite the sonic shift, the album and its singles still made a mark on the country charts, but it would be the last time.

Olivia Newton—John was about to become a bona fide pop megastar, a true crossover artist setting the template for the likes of Shania, Sheryl and Taylor.

Let’s get animal

A rollerskating space musical riffing on Greek mythology and co-starring Gene Kelly would have been exactly nobody’s prediction for Newton—John’s next move. Xanadu (1980) did not exactly set the box ofiice alight, but its soundtrack, recorded with Electric Light Orchestra and including guest spots from Kelly and Cliff Richard, was a top-5 hit in the US, UK and Australia, and it smashed out five US hits, including the sublime chart—topper ‘Magic’.

And, it‘s got to be said: the iconic title track ends in an otherworldly climax that rates alongside the final bars of Summer Nights as notes no mere mortal should attempt to hit at karaoke (but we shall forever fuel ourselves with cheap sparkling wine and give it a red—hot go, against all good advice).

Then came ‘Physical’.

To be clear, O1ivia’s previous number ls were huge hits. Huge. ‘Physical’, however, was something else altogether.

It was a pop juggernaut. Ten weeks in the top slot earned it the title of longest-running number 1 hit in Billboard history at the time, an honour it shared with Debby Boone’s ‘You Light Up My Life’ (1977). It would take another decade before anyone could top it.

The song’s success is all the more extraordinary when you consider the times in which it happened. Released in September 1981, ten months after American voters ushered in the conservative Reagan era, the Olivia Newton—John of ‘Physical’ would’ve made post-makeover Sandy from Grease blush.

With her signature blonde hair chopped short, the formerly wholesome singer appeared on the single cover splashing about in a wet t—shirt, her face frozen in pure ecstasy.

The sweatband around her head tried to imply her expression might be down to a spot of exuberant callisthenics, but Physical's lyrics made it clear: this was all about sex. I took you to an intimate restaurant / Then to a suggestive movie, she sings.

There’s nothin’ left to talk about / Unless it’s horizontally ...

They call it reinventing yourself,

Newton-John quipped in an interview around the song’s fortieth anniversary. I wasn’t doing it on purpose. It just was the song that I was attracted to and the album. But I feel very fortunate that I had the opportunity to record it.

The suggestive lyrics were obtuse enough that five—year—olds like me could sing along to the earworm of a chorus while remaining oblivious to the true intent behind the Words: a woman declaring on the radio that, yep, she wants it.

Even Olivia didn’t quite cotton on to just how racy the song was until it was too late. After it was finished, that’s when I freaked out,

she told Entertainment Tonight in 2021. I called my manager and said - We have to, we have to kill it. Let’s stop it because I think I’ve gone too far. And he said, It’s already on the charts, doll. it’s doing really well, We can't stop it . . . Very often the things you are most afraid of, or tentative about doing, are the things you need to do.

Watch the accompanying music video and the word tentative

doesn't exactly spring to mind. Newton-John ran towards the sensual themes, turning the perception of female sexuality on its head in the process.

The first seconds open on a naked man breaking several health codes on a gym exercise bike (actually, he’s wearing barely—there bikini briefs, but he most definitely didn’t put a towel down before working out). A procession of spectacularly fit abs, biceps and buttocks ensue. It’s not until the video’s final minute that we actually see the faces of these disembodied studs: it’s overt, unashamed objectification through the Female (and homosexual) gaze.

And, surprisingly, middle America was here for it.

That didn’t stop it getting banned in some US states, but given the political environment of the day, the fact that the blacklist wasn't more widespread is quite extraordinary. The video's real kicker comes at the punchline: after systematically ogling and stroking the men in the gym, Newton—John finds herself cut out of the picture as two of the men head off to the locker room to, presumably, get physical with each other.

The image of two men wearing what scarcely qualify as Speedos holding hands, and another equally underdressed couple with arms around waists, hands dangerously straddling lower back and upper cheek, was pretty ground—breaking stuff.

Perhaps it was Olivia’s sweet—as—pie public persona or the comic tone of the clip — a bit of Benny Hill—style fast-motion, knowing looks to camera with camp tongue planted firmly in cheek — but she got away with it. Maybe if the video had ended with her heading off to enjoy a post—Workout orgy, people would have rioted at the sight of a woman owning her sexuality. But by the end of the song, the singer is left with the gym's least muscle—bound member, Joe Public’s fragile ego remains intact and the average punter can still kid himself that he stands a chance with Olivia.

No, rather than be branded a harlot, she managed the biggest hit of her career. I felt a little embarrassed to be banned,

she admitted to Fox News in 2021. But looking back now I go, That was great. It got attention.

You'd have to imagine a certain young upstart from Michigan noticed the way sex, controversy and the emerging music video discipline could get people talking about you. Four short years later, us kids were innocently crooning like a virgin, touched for the very first time

in the back seat of the car after Madonna grabbed the baton passed by ‘Physical’.

Eventually, female artists discarded entendres altogether, free to simply declare that they just love to f*ck (here's looking at you, WAP).

So yeah, Olivia took the sex sells philosophy and cashed in big time. ‘Physical’ was Americas biggest song in 1982 (and number 1 in Australia, 7 in the UK), and even today it is the eleventh—biggest Billboard hit of all time.

The album of the same name was a global smash. The synth-led production, totally fresh at the time, later came to millions of copies, the album completed Newton—John’s transition from country crooner to pop superstar, proving she could top even her own considerable success in a different genre — decades before Taylor Swift followed suit.

Oh, and remember how Beyonce blew everyone’s minds with her self-titled visual album in 2013? You’ll be interested to know that Olivia’s Physical, a video album, followed the LP in 1982. Debuting as a prime—time TV special (it drew over one—third of the total viewing audience] before being released commercially on VHS, Olivia Physical crafted clips for each song on the LP and won Video of the Year at the Grammys.

Releasing it into a world where MTV was just months old, Newton-John was among the vanguard of artists who recognised and helped to elevate the status of the music clip in pop. And she turned sweatbands into a Fashion statement, for christ’s sake.

She’s had lyrics tackling serious issues like AIDS (Love and Let Live, 1988) and conservation (The Promise (The Dolphin Song), 1981), backing up her beliefs with action.

Proceeds from her music went to cancer research, and she was a keen environmentalist and animal lover, even boycotting performing in Japan back in the '70s because of dolphin slaughter.

And back when pop stars were usually just pop stars (because they could still make considerable coin from music alone}, Olivia added businesswoman to singer—songWriter—actor through her businesses Koala Blue and the Gala health retreat. Now, every chart act is all about extending their brand

.

When news of Newton-John’s death broke in August this year, a dozen of her tracks soared into the Billboard Digital Song Sales chart, matching Whitney Houston’s posthumous record for most chart entries in a single week by a female artist.

With over 100 million global sales and counting, Newton-John’s legacy means that she'll never truly be gone. She’ll be remembered forever, literal pop royalty — the late (been Elizabeth II) knew as much, and made the singer a dame in 2020 for her charity and entertainment work.

When Olivia became an Australian citizen in 1981 at the height of her fame, prime minister Malcolm Fraser performed a national service by fast-tracking her application so that we could make our love affair with her official.

Olivia Newton-John managed to buck expectations in another way: Aussies love to cut clown their most successful artists. The cultural cringe

sees us feign utter embarrassment at our pop exports, so we diminish and disown them to make sure they don't get too big for their go-go boots. Not merely dodging the tall poppy syndrome, Newton-John was always our Livvy

, a constant source of national pride and affection. Australia, and the world, adored her unconditionally.

We love you, Olivia. We honestly love you.