Newton-John's Father

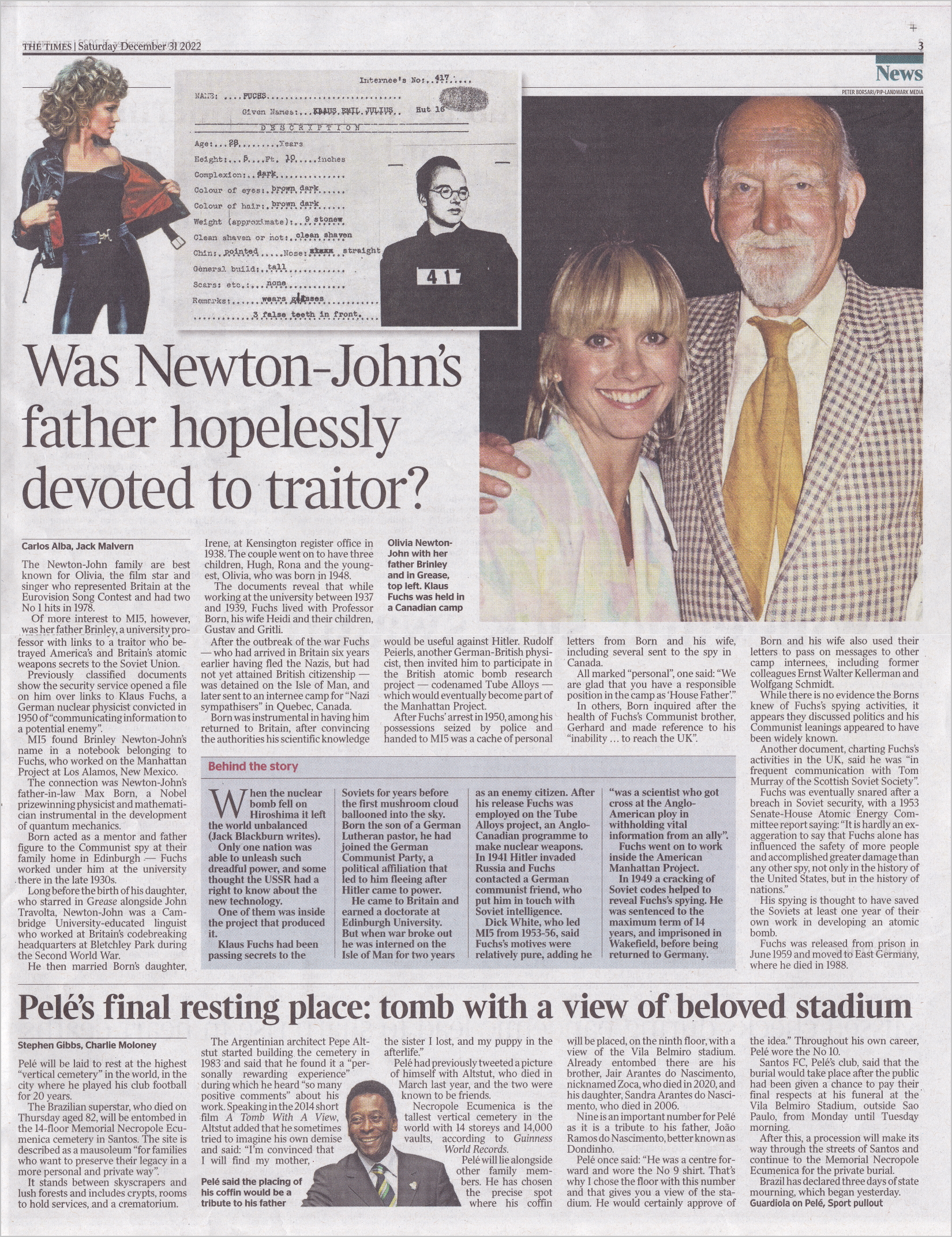

The Newton-John family are best known for Olivia, the film star and singer who represented Britain at the Eurovision Song Contest and had two No 1 hits in 1978.

Of more interest to MI5, however, was her father Brinley, a university professor with links to a traitor who betrayed America’s and Britain’s atomic weapons secrets to the Soviet Union.

Previously classified documents show the security service opened a file on him over links to Klaus Fuchs, a German nuclear physicist convicted in 1950 of “communicating information to a potential enemy”.

MI5 found Brinley Newton-John’s name in a notebook belonging to Fuchs, who worked on the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos, New Mexico.

The connection was Newton-John’s father-in-law Max Born, a Nobel prizewinning physicist and mathematician instrumental in the development of quantum mechanics

Born acted as a mentor and father figure to the Communist spy at their family home in Edinburgh — Fuchs worked under him at the university there in the late 1930s.

Long before the birth of his daughter, who starred in Grease alongside John Travolta, Newton-John was a Cambridge University-educated linguist who worked at Britain’s codebreaking headquarters at Bletchley Park during the Second World War.

He then married Born’s daughter, Irene, at Kensington register office in 1938. The couple went on to have three children, Hugh, Rona and the youngest, Olivia, who was born in 1948.

The documents reveal that while working at the university between 1937 and 1939, Fuchs lived with Professor Born, his wife Heidi and their children, Gustav and Gritli

After the outbreak of the war Fuchs — who had arrived in Britain six years earlier having fled the Nazis, but had not yet attained British citizenship — was detained on the Isle of Man, and later sent to an internee camp for “Nazi sympathisers” in Quebec, Canada.

Born was instrumental in having him returned to Britain, after convincing the authorities his scientific knowledge would be useful against Hitler. Rudolf Peierls, another German-British physicist, then invited him to participate in the British atomic bomb research project — codenamed Tube Alloys — which would eventually become part of the Manhattan Project

After Fuchs’ arrest in 1950, among his possessions seized by police and handed to MI5 was a cache of personal letters from Born and his wife, including several sent to the spy in Canada.

All marked “personal”, one said: “We are glad that you have a responsible position in the camp as ‘House Father.’ In others, Born inquired after the health of Fuchs’s Communist brother, Gerhard and made reference to his “inability . . . to reach the UK”.

Born and his wife also used their letters to pass on messages to other camp internees, including former colleagues Ernst Walter Kellerman and Wolfgang Schmidt.

While there is no evidence the Borns knew of Fuchs’s spying activities, it appears they discussed politics and his Communist leanings appeared to have been widely known.

Another document, charting Fuchs’s activities in the UK, said he was “in frequent communication with Tom Murray of the Scottish Soviet Society”.

Fuchs was eventually snared after a breach in Soviet security, with a 1953 Senate-House Atomic Energy Committee report saying: “It is hardly an exaggeration to say that Fuchs alone has influenced the safety of more people and accomplished greater damage than any other spy, not only in the history of the United States, but in the history of nations.”

His spying is thought to have saved the Soviets at least one year of their own work in developing an atomic bomb.

Fuchs was released from prison in June 1959 and moved to East Germany, where he died in 1988.

Behind The Story

When the nuclear bomb fell on Hiroshima it left the world unbalanced (Jack Blackburn writes).

Only one nation was able to unleash such dreadful power, and some thought the USSR had a right to know about the new technology.

One of them was inside the project that produced it.

Klaus Fuchs had been passing secrets to the Soviets for years before the first mushroom cloud ballooned into the sky. Born the son of a German Lutheran pastor, he had joined the German Communist Party, a political affiliation that led to him fleeing after Hitler came to power.

He came to Britain and earned a doctorate at Edinburgh University. But when war broke out he was interned on the Isle of Man for two years as an enemy citizen. After his release Fuchs was employed on the Tube Alloys project, an Anglo-Canadian programme to make nuclear weapons. In 1941 Hitler invaded Russia and Fuchs contacted a German communist friend, who put him in touch with Soviet intelligence.

Dick White, who led MI5 from 1953-56, said Fuchs’s motives were relatively pure, adding he “was a scientist who got cross at the Anglo-American ploy in withholding vital information from an ally”.

Fuchs went on to work inside the American Manhattan Project

In 1949 a cracking of Soviet codes helped to reveal Fuchs’s spying. He was sentenced to the maximum term of 14 years, and imprisoned in Wakefield, before being returned to Germany.