Olivia Country Gal at heart

By CLIFFORD TERRY Chicago Tribune

When Olivia Newton-John was named 1974 Female Vocalist of the Year by the Country Music Association, the predictable hooting from down-home fans was as loud and clear as if someone had certified that John Denver was indeed a country boy or that Hoyt Axton really didn’t have bony fingers.

Their contention, of course, was that Miss Newton-John a product of Cambridge, England, and Melbourne, Australia was about as “country” as Claridges. That any dues she had paid had been in pounds and shillings. That she was more 1974 shiny Rolls Royce than 1954 rusted-out Chevy, more Pimm’s Cup than Pabst Blue Ribbon.

The 1974 Vocalist of the Year, huffed a writer for the Nashville Tennessean, “couldn’t drawl with a mouth full of biscuits,” and another critic went on about her “plastic personality-kid routine” and her “coy and cutesy approach” to C & W music-reminiscent of “someone out for an evening of slumming in country bars.”

But unlike the people in her songs, Olivia Newton-John is not exactly crying her eyes out over all this. For every detractor, she has a countless number of fans out there who have made her their own special hyphenated honey. Reportedly the biggest seller of any woman singer in the country, including fellow Australian Helen Reddy, she was the first female to hit on three successive No. 1 singles on the top-pop charts, turned out in gold records, and collected three Grammies.

Still, all that flak over her ‘74 country- music award must have hurt. Asked for her reaction, she grimaces in mock horror and lets loose a rather loud scream. She is sitting in tier business office on Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles, just across the street from the Celebrity Club of “hip hypnotist” Pat Collins and worlds apart from Tootsie’s Orchid Lounge, the original Grand Old Opry’s unofficial annex.

“I’ve just recorded an album in Nashville my first there,” she is saying, “and people told me all that criticism has been forgotten, that it was all blown up out of proportion, that there were only two or three people who were objecting. I think it was understandable in a way. Someone new comes along who isn’t even American and steals an award that was theirs, and it gets up their noses a bit. “But music has to expand. You can’t keep it in a bag. You’ve got to open it out, and I think it’s happening. Anyway, I never claimed to be a country singer. And I certainly didn’t put myself up for the award or vote for myself.”

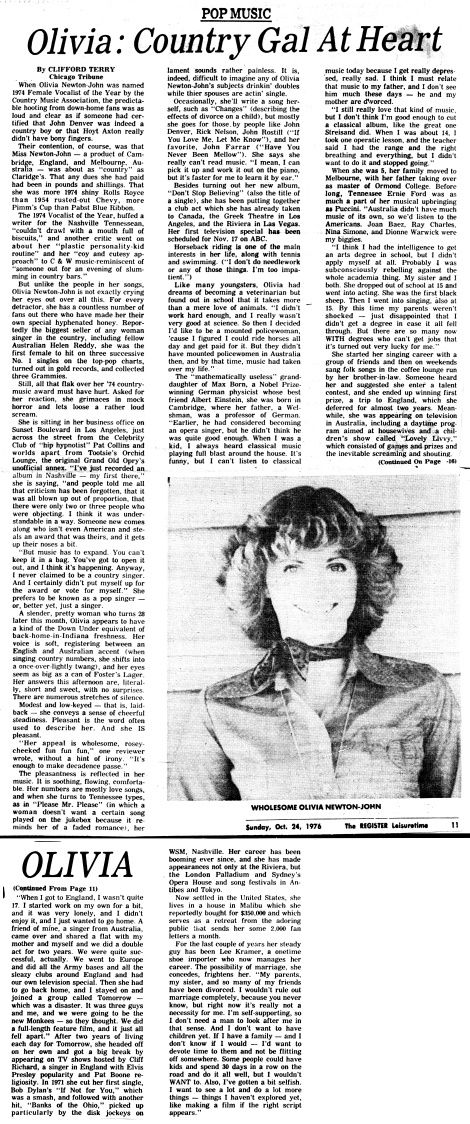

She prefers to be known as a pop singer or, better yet, just a singer. A slender, pretty woman who turns 28 later this month, Olivia appears to have a kind of the Down Under equivalent of back-home-in-Indiana freshness. Her voice is soft, registering between an English and Australian accent (when singing country numbers, she shifts into a once-over-lightly twang), and her eyes seem as big as a can of Foster’s Lager. Her answers this afternoon are, literally, short and sweet, with no surprises. There are numerous stretches of silence. Modest and low-keyed that is, laid- back she conveys a sense of cheerful steadiness. Pleasant is the word often used to describe her. And she IS pleasant.

“Her appeal is wholesome, rosey- cheeked fun fun fun,” one reviewer wrote, without a hint of irony. “It’s enough to make decadence passe.” The pleasantness is reflected in her music. It is soothing, flowing. comfortable. Her numbers are mostly love songs, and when she turns to Tennessee types, as in “Please Mr. Please” (in which a woman doesn’t want a certain song played on the jukebox because it reminds her of a faded romance), her lament sounds rather painless.

It is, indeed, difficult to imagine any of Olivia Newton-John’s subjects drinkin’ doubles while their spouses are actin’ single Occasionally, she’ll write a song herself, such as “Changes” (describing the effects of divorce on a child), but mostly she goes for those by people like John Denver, Rick Nelson, John Rostill (“If You Love Me, Let Me Know”), and her favorite, John Farrar (“Have You Never Been Mellow”). She says she really can’t read music. “I mean, I can pick it up and work it out on the piano, but it’s faster for me to learn it by ear.”

Besides turning out her new album, “Don’t Stop Believin” (also the title of a single), she has been putting together a club act which she has already taken to Canada, the Greek Theatre in Los Angeles, and the Riviera in Las Vegas. Her first television special had been scheduled for Nov, 17 on ABC.

Horseback riding is one of the main interests in her life, along with tennis and swimming. (“I don’t do needlework or any of those things I’m too impatient.”) Like many youngsters, Olivia had dreams of becoming a veterinarian but found out in school that it takes more than a mere love of animals. “I didn’t work hard enough, and I really wasn’t very good at science. So then I decided I’d like to be a mounted policewoman, ‘cause I figured I could ride horses all day and get paid for it. But they didn’t have mounted policewomen in Australia then, and by that time, music had taken over my life.”

The “mathematically useless” granddaughter of Max Born, a Nobel Prize- winning German physicist whose best friend Albert Einstein, she was born in Cambridge, where her father, a Welshman, was a professor of German. “Earlier, he had considered becoming an opera singer, but he didn’t think he was quite good enough. When I was a kid, I always heard classical music playing full blast around the house. It’s funny, but I can’t listen to classical music today because I get really depressed, really sad. I think I must relate that music to my father, and I don’t see him much these days he and my mother are divorced.”

“I still really love that kind of music, but I don’t think I’m good enough to cut a classical album, like the great one Streisand did. When I was about 14, I took one operatic lesson, and the teacher said I had the range and the right breathing and everything, but I didn’t want to do it and stopped going.”

When she was 5, her family moved to Melbourne, with her father taking over as master of Ormond College. Before long, Tennessee Ernie Ford was as much a part of her musical upbringing as Puccini. “Australia didn’t have much music of its own, so we’d listen to the Americans. Joan Baez, Ray Charles, Nina Simone, and Dionne Warwick were my biggies.”

“I think I had the intelligence to get an arts degree in school, but I didn’t apply myself at all. Probably I was subconsciously rebelling against the whole academia thing. My sister and I both. She dropped out of school at 15 and went into acting. She was the first black sheep. Then I went into singing, also at 15. By this time my parents weren’t shocked, just disappointed that I didn’t get a degree in case it all fell through. But there are so many now WITH degrees who can’t get jobs that it’s turned out very lucky for me.”

She started her singing career with a group of friends and then on weekends sang folk songs in the coffee lounge run by her brother-in-law. Someone heard her and suggested she enter a talent contest, and she ended up winning first prize, a trip to England, which she deferred for almost two years. Meanwhile, she was appearing on television in Australia, including a daytime program aimed at housewives and a children’s show called “Lovely Livvy,” which consisted of games and prizes and the inevitable screaming and shouting.

“When I got to England, I wasn’t quite 17. I started work on my own for a bit, and it was very lonely, and I didn’t enjoy it, and I just wanted to go home. A friend of mine a singer from Australia, came over and shared a flat with my mother and myself and we did a double act for two years. We were quite successful, actually. We went to Europe and did all the Army bases and all the sleazy clubs around England and had our own television special. Then she had to go back home, and I stayed on and joined a group called Toomorrow which was a disaster. It was three guys and me, and we were going to be the new Monkees so they thought. We did a full-length feature film, and it just all fell apart.”

After two years of living each day for Tomorrow, she headed off on her own and got a big break by appearing on TV shows hosted by Cliff Richard, a singer in England with Elvis Presley popularity and Pat Boone religiosity. In 1971 she cut her first single, Bob Dylan’s “If Not for You,” which was a smash, and followed with another hit, “Banks of the Ohio,” picked up particularly by the disc jockeys on WSM, Nashville.

Her career has been booming ever since, and she has made appearances not only at the Riviera, but the London Palladium and Sydney’s Opera House and song festivals in Antibes and Tokyo. Now settled in the United States, she lives in a house in Malibu which she reportedly bought for $350,008 and which serves as a retreat from the adoring public who sends her some 2,000 fan letters a month.

For the last couple of years her steady guy has been Lee Kramer, a one time shoe importer who now manages her career. The possibility of marriage, she concedes, frightens her. “My parents, my sister, and so many of my friends have been divorced. I wouldn’t rule out marriage completely, because you never know, but right now it’s really not a necessity for me. I’m self-supporting, so I don’t need a man to look after me in that sense. And I don’t want to have children yet. If I have a family and I don’t know if I would I’d want to devote time to them and not be flitting off somewhere. Some people could have kids and spend 30 days in a row on the road and do it all well, but I wouldn’t WANT to.

Also, I’ve gotten a bit selfish. I want to see a lot and do a lot more things, things I haven’t explored yet, like making a film if the right script appears.”